How Do We Want to Be Remembered?

Let’s not be the Generation that dishonored our history

Brooksville is at a crossroads. Most of us are proud of our community and understand the valuable and unusual contribution we make to our state and national history. Investors are recognizing the unique character of downtown and are looking for properties so they can be part of it. But this attention is accompanied by danger – there are no protections in place to guard what makes us special.

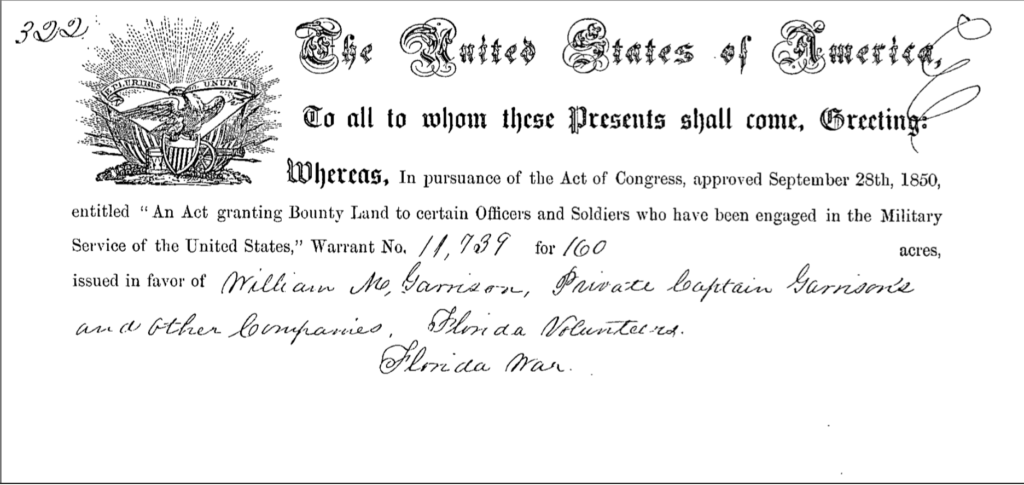

Until last month, City Council had no ordinance in place for code enforcement for commercial properties. If you had a dangerous situation at a residence, they could require you to make it safe. But that was not the case for commercial properties. That lack of protections led to what now looks like will result in the demolition of the Garrison House on South Brooksville Avenue. This oldest house in the county, built in the early 1840s, was home to the William Garrison family. The Garrisons moved to Brooksville and received their land as part of the Armed Occupation Act. They served in early County government and helped found the city.

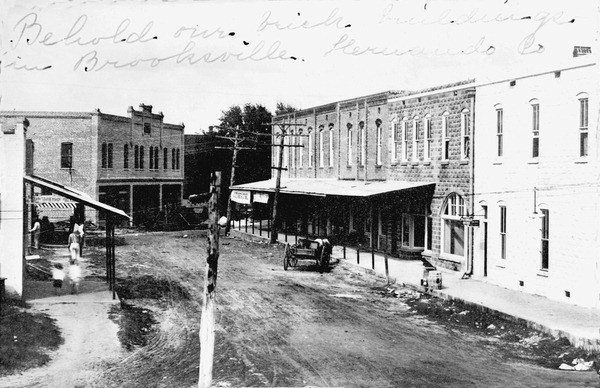

In the early 1900s, the Garrisons sold it to AA Haskell, a photographer who set up his studio in the house and lived there as well. The photographs developed in that home gave us most of the aerial shots we have of Brooksville between 1911-1930, a treasure beyond measure. When Haskell died, the house was bought by Edward MacKenzie, a beloved lawyer. When lawlessness reigned in Hernando County in 1932, MacKenzie beat an incumbent judge and brought law and order back to Brooksville.

The house is important because it is a “shanty,” the kind of house that most settlers would have lived in. While homes like Chinsegut and May-Stringer show us how the upper crust lived, the Garrison House represents the two room existence of most early pioneers. The Garrisons and others like them, left comfort elsewhere to move to Brooksville to make a better life for themselves, but sacrificed an easier life in the process. The house was added onto as money allowed, with an addition in the late 1800s and another in the early 1900s. The wood, doorknobs, and hardware didn’t match, because the owners added them as they could afford them. The house is a testament to perseverance of the pioneer spirit.

When the current owners purchased it in the 1980s, it was in great condition. They bought the property because they wanted a parking lot instead of the house. Asbestos meant demolition would be very expensive and they offered to give the house to the Hernando Museum Association if they would move it. Jan Knowles and Virginia Jackson (who both went on to win the city’s Great Brooksvillian award) wrote a grant to the State and went to Tallahassee to testify before the Legislature for the project. Jan was having serious medical issues at the time and special accommodations were needed for her to travel, but she made the trip anyway.

Despite Jan and Virginia’s work, the grant did not make it through appropriations, and the house continued to sit vacant and deteriorate as no efforts were made to maintain it. Sometimes a behavior can be immoral without being illegal.

Contrast this with another historic structure in Brooksville. When the Hensley family bought the May-Stringer House it was in pretty bad shape. They were going to demo it and build a chiropractic office there. But they saw the value in the house and instead facilitated and helped finance the purchase of the home to what is now the Hernando Heritage Museum. They built their chiropractic office elsewhere and preserved the house. We all benefit from their community-minded foresight and generosity.

So this week the Garrison House demolition began. This is a textbook case of what historic preservationists call Demolition by Neglect. Owners of historic properties are caretakers and get to decide if their community will look better or worse when the next caretaker takes over. But we as residents, elected officials, and lovers of Brooksville also play a part. We decide if we want to put regulations in place to protect our historic city or if we don’t.

Over a decade ago, the Brooksville City Council approved the creation of a Historic Preservation Board, which would help protect historic structures. But the Board was never populated. In the past, staff has said it would be hard to find people to serve on it. Maybe we should test that theory by letting people apply. How do we want our generation to be remembered? As the one that allowed a historic downtown to be demolished by neglect? Or as one that treasured the gift we’ve been given by the generations before us and passed it on intact to those coming after? The choice is ours and the stakes are huge.